Developing Loving Kindness (Mettā bhāvanā)

Let's learn how to practise a type of meditation which will also be of great benefit in developing the right attitude in all kinds of social situations. It is called developing loving-kindness (mettā bhāvanā)

loving-kindness (mettā),

compassion (karunā),

sympathetic joy (muditā)

and equanimity (upekkhā).

loving-kindness meditation is the most popularly practised of these.

May all of you experience the ultimate peace within!

May all beings be happy!

May all of you be well and happy!

Mindfulness of Death (Maraṇānussati)

Let's learn how to practise a type of meditation which will also be of great benefit in developing the right attitude in all kinds of social situations. It is called developing loving-kindness (mettā bhāvanā)

loving-kindness (mettā),

compassion (karunā),

sympathetic joy (muditā)

and equanimity (upekkhā).

loving-kindness meditation is the most popularly practised of these.

The practice is also known as appamaññā, which means unlimited, because the application of loving-kindness must be infinite or boundless. Mettā means pure love, unconditional and undiscriminating. One who again and again extends boundless love to all beings everywhere will generate and fill the mind with pure mental energies which subtly change its attitude. If there are any negative feelings present when we send our loving kindness to others - selfish attachment, for example - then it is not pure Mettā. We cannot restrict such love only to some people or send it only to our own family or friends. It belongs to all sentient beings.

There are many kinds of love in human society - a mother's love for her child, a husband's love for his wife, love between brothers and sisters, love between friends, yet none of these are Mettā. Why? Because human love is based on attachment. We give love in the expectation of getting something back, a return of affection at the very least. Loving kindness must be given freely; it’s a one-way ticket. But there is a return half even so, in that by giving love to all beings without exception, we experience so much more peace, happiness and harmony within ourselves. This in turn we reinvest by sharing it and dedicating its result to the welfare of others.

Whenever you have problems with others, difficulties with those you work with or live with, then for your own well-being and theirs you should send loving kindness to that particular person. Mettā is like telepathy, you can communicate it mentally and the effect will be felt by the other person so that his or her attitude changes. Of its power the Buddha himself said:

Truly, hatred never ceases through hatred in this world;

Through love alone it ceases.

This is an ancient law.

(Dhammapada v.5)

Loving kindness meditation is a most powerful antidote for anger and it can and should be practised at all times and in every situation as it will help you to live your life happily and harmoniously. Let's suppose that someone acted badly towards me or verbally abused me twenty-five years ago and to this day I cannot let go of the memory of what was said or done to me. I still feel angry about it after all this time. However much I punish him in my head, it's really me that suffers, not the other person. Had I given loving kindness to him at that moment twenty-five years ago, I would not now be still suffering from negative feelings.

Those who practise Insight meditation understand that if one generates negative feelings, these produce negative energies that cause oneself to suffer and affect others badly too. But by suffusing your mind and body with peace and happiness through this meditation, you will create and emanate pure energies that will be beneficial for all.

The aim of Insight meditation is to purify the mind. By the end of each session this has been achieved to a certain extent and so the meditator experiences some degree of happiness and peace and is inclined to want to share these feelings with others. Sending loving kindness is an ideal way to do this. So long as negative thoughts or feelings such as attachment, jealousy or selfishness are present, you cannot give pure Mettā to others. Therefore, you need to purify your heart by first directing loving kindness towards yourself. This is not at all a selfish thing to do. Only after having purified yourself are you fit to send it to others.

We begin our practice by visualising ourselves as we are in this room and getting in touch with that wish to be happy which is common to us all. Forget about the negativity that many of us feel towards ourselves, forget about doubt. Just open your heart with confidence in the practice and let it fill you with this positive energy. If it helps you to verbalise good wishes for yourself, then really mean what you say:

May I be free from anger and ill will.

May I be free from fear and anxiety.

May I be free from suffering and pain.

May I be free from ignorance and desire.

May I be happy and peaceful.

May I be harmonious.

May I be liberated from bondages such as greed, anger and delusion.

May I realize the Nibbānic peace within.

When you get in touch with this goodwill towards yourself, you are sharing in the natural impulse of all beings. The next step, then, is to break down the barrier we erect between ourselves and others by opening our hearts to them and wishing them equally what we have wished for ourselves:

May all beings be free from anger and ill will.

May all beings be free from fear and anxiety.

May all beings be free from suffering and pain.

May all beings be free from ignorance and desire.

May all beings be happy and peaceful.

May all beings live in harmony.

May all beings be liberated from bondages such as greed, anger and delusion.

May all beings realize the Nibbānic peace within.

Next we have to share our peace and happiness with those near and dear to us such as parents, teachers, relatives and friends. If there is someone you know who is ill or in difficulty, now is the opportunity to give your Mettā to that particular person. Doing this will help reduce their suffering and pain. Then, finally, dedicate the good of your practice to the welfare and spiritual advancement of all beings:

May they be happy!

May they be happy!

May they be happy!

Loving kindness meditation and Insight meditation may also be practised so as to reinforce each other. When you are not happy with people or a situation, for example, first try to be aware of your feelings and, if they are strong, begin by giving loving kindness to yourself. Once you are calm, wish the other person well. If you make use of both practices in your life, it will be very helpful in enabling you to live in harmony with others and at peace with yourself.

During our time together here I have spoken at length about many things in order that you might understand the Buddha's teaching and develop awareness and wisdom. You may not have fully understood it all, you may not be prepared to accept everything, but this does not matter. If you have grasped just one or two things and found them beneficial, then be sure to make good use of them and leave the rest for the time being. Some things you may need to use later and some not at all. It's rather like going to a shopping centre or supermarket. Although there are a great variety of things on display, you don't buy everything you see but only what you need that day. The rest you will leave for another time; indeed, some things you may never need.

The most important thing for each one of you to do is maintain your practice. A serious meditator will practice twice a day. One hour in the morning and one hour in the evening would be most beneficial. As most of you are living the householder's life, you may not have time to practise for so long. If this is the case, then I recommend half an hour's practice morning and evening. If that is still too difficult, then sit for at least fifteen minutes morning and evening. If you do this every day, it will help you to maintain your practice; but don't neglect to apply Insight to your daily life as well. It will also be helpful for you if you find the time once a week to sit for least one hour by yourself or with another meditator.

During the retreat I have praised this technique as a good and effective way to achieve total liberation and have advised you to practise it for your own benefit and happiness. In saying this I did not mean to imply that other techniques are not effective. It is just as if I were to praise my mother and say again and again how good and kind and compassionate she is. In making this claim I am not implying that your mother is not good or that I dislike her or think my mother is better than yours. It is simply that in my experience my mother is good whilst in your eyes your mother is good. Both are good, of course, and so are the mothers of other people. There are many who teach according to their own understanding and have different approaches and techniques. It is unreasonable to say that only one method is good and others are not. The real issue is whether a certain practice is suitable to one's individual temperament and needs. Some people may benefit from this technique whilst others will benefit from another. The Buddha never claimed that his teachings were good and beneficial for all, but he did say that they would benefit many. No technique or teaching can be said to be universally applicable.

I would like to encourage all of you to keep practising until the path of insight becomes your way of life and your way in life. Then you can live happily and remain in harmony with yourself and others. At the beginning of this course I said that the Buddha is regarded as a great physician who prescribed the Noble Eightfold Path and the practice of Insight meditation as an effective way of healing the universal disease of suffering. Interest¬ingly the English word meditation is derived from the Latin word mederi, which means ‘to heal’. So, if you want to rid yourself of the disease of suffering, meditation is the right word for what you must do and is an effective medicine.

In conclusion, I would like to say that if you want to understand the Buddha, then try to understand yourself by practising the Noble Eightfold Path he taught. This path is the path for your own happiness and well¬being, this is the path for your liberation from the bondages of greed, hatred and delusion and from suffering. This is the path leading to Enlightenment and Nibbāna.

May all of you experience the ultimate peace within!

May all beings be happy!

May all of you be well and happy!

______________________________

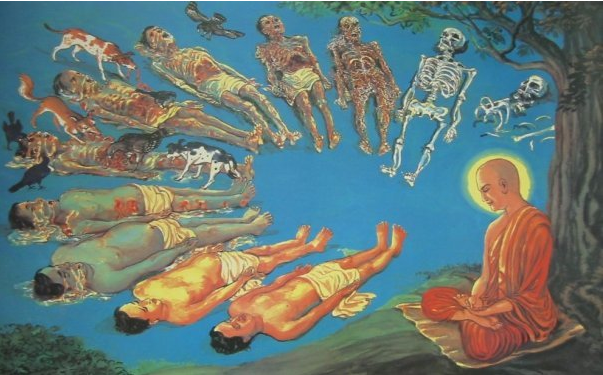

Mindfulness of death is a Vipassana practice that the meditator should develop while holding the perception of impermanence, suffering and the phenomenality of selfhood in mind. It is one of the four subjects grouped among the ten recollections that are most suitable for a person of intellectual disposition. In the context of rebirth, death is defined as the cutting off of the life-faculty of one form of existence. Therefore, the word is not intended to denote any of the following three types of death: complete cessation of life, that is the passing of the Arahant's final manifestation in the world of change; momentary dying, that is, the moment to moment breaking up of the mental and physical processes; the death of non-breathing objects, an expression commonly used in speaking of a dead tree, inert metal and so on.

According to the Abhidhamma, the advent of death is fourfold:

1) Through the expiration of the life span (āyukhaya). This is the kind of death that comes about for beings in those realms of existence where the life-span is bounded by a definite limit. In the human realm this should be understood as death in advanced old age due to natural causes. If the productive kamma is still not exhausted when death takes place, then the kammic force can generate another rebirth on the same plane or on some higher plane according to how one has lived previously.

2) Through expiration of the productive kammic force (kamma-khaya). This is the kind of death that take place when the kamma generating rebirth expends its force though the normal life-span and there are otherwise favourable conditions for the prolongation of life.

3) Through the simultaneous expiration of both (ubhayattha).

4) Through the intervention of a destructive kamma (upeccheda-kamma). This is a term for the death that occurs even before the expiration of the life-span.

According to the Abhidhamma, the advent of death is fourfold:

1) Through the expiration of the life span (āyukhaya). This is the kind of death that comes about for beings in those realms of existence where the life-span is bounded by a definite limit. In the human realm this should be understood as death in advanced old age due to natural causes. If the productive kamma is still not exhausted when death takes place, then the kammic force can generate another rebirth on the same plane or on some higher plane according to how one has lived previously.

2) Through expiration of the productive kammic force (kamma-khaya). This is the kind of death that take place when the kamma generating rebirth expends its force though the normal life-span and there are otherwise favourable conditions for the prolongation of life.

3) Through the simultaneous expiration of both (ubhayattha).

4) Through the intervention of a destructive kamma (upeccheda-kamma). This is a term for the death that occurs even before the expiration of the life-span.

The Method of Meditation

Both kinds of death are contemplated m this practice and then recollection constitutes mindfulness of death. In order to develop it, one should sitin seclusion and focus attention on the thought, ‘death will take place, the life-faculty will be cut off’, or more simply ‘death, death’ (maraṇaṃ, maraṇaṃ). The repetition of any of these terms will form the preliminary exercise. To practise rightly, one's mindfulness should be accompanied by a sense of urgency, as of a ‘life or death situation’. One should avoid recalling the death of individuals, whether loved ones, enemies or those towards whom one was indifferent. Sorrow arises in recalling the death ofbeloved ones; gladness or an unsympathetic feeling arises in recalling the death of hostile persons; the feeling of urgency does not arise in recalling the death of people towards whom one is indifferent; but fear arises at the thought of one's own death. By proceeding in the right way, the hindrances disappear, mindfulness is established with death as its object and, ace concentration is attained.

If this is of no benefit, one may contemplate death m these eight ways:

1) It should be borne in mind that just as an armed murderer comes upon one saying ‘I’ll kill you’, so death approaches and threatens all living beings.

2) Or one may consider, ‘As all prosperity and achievement m this world comes to an end, so too does a prosperous life’.

3) One may infer one’s own death from that of others. ‘All the great ones in the past who had magnificence, merit, might, power and learning, have passed away in death; those who attained the highest state of spiritual progress, like Buddhas and Arahants, have passed away too; like those, I myself have also to die.’

4) ‘At all events, death is inevitable because this body is subject to all the causes of death, such as the many hundreds of diseases as well as other external dangers. At any moment any of these may beset the body and cause it to perish.’ Thus death should be recollected by way of the body and its liability to many dangers.

5) The life of beings is bound up with inhalation and exhalation, with the four postures, with the proper temperature and with food. Life continues only while it is supported by the regular functioning of the breath; when this process ceases, one dies. Life proceeds while it is supported by walking, standing, sitting and lying down; it also requires just the right measure of heat and cold and it must be supported by food. If any of these conditions are unbalanced or fail, life comes to an end. Thus should death be recollected by considering the frailty of life and its dependence upon these things.

6) Life in this world is uncertain because it cannot be determined as regards time, cause, place or destiny. It cannot be reduced to rule. Life may fail at any point or any moment. Sickness also cannot be determined, as for example ‘Of this type of sickness alone beings die but not another’, for people die of any kind. The time of death is also unknown since it cannot be determined. The place where the body should lie is also unknown and the place one will take rebirth. Thus death should be recollected by considering that these five things are uncertain.

7) The life of human beings is of short duration. Even if one were to live to a hundred, it still comes to an end.

8) The life of a living being lasts only for the period of a single thought moment. As soon as that thought has ceased, the being is said to have ceased.

Life, personality, pleasure and pain

Are joined in a single conscious moment;

Suddenly it passes, never to return.

(Visuddhimagga VIII.38)

As long as continuity of consciousness lasts, the continuity of a life proceeds. When the consciousness ceases to function in an individual organism, life also ceases. Thus should mindfulness of death be developed by concentrating on the nature of consciousness and the little deaths and births it brings moment by moment.

When the meditator contemplates death in one of these eight ways, mindfulness is established with death as its object; the hindrances disappear and the jhānic factors bring tranquillity. Death being a natural occurrence, and often the cause of anxiety, mindfulness of it is productive only if access concentration and the jhānic factors do not lead to absorption. Even a moment of this meditation practice with proper attention bears great fruit. One who devotes himself to this meditation is always vigilant and takes less delight in the phenomenal world. One gives up hankering after life; one censures evil doing. One is free from craving as regards the requisites of life; one’s understanding of impermanence becomes lucid. In consequence of these things one realizes the suffering and impersonal nature of existence. At the time of death one is devoid of fear and remains mindful and self-possessed. If one fails to attain to the deathless (nibbāna) in this present life, upon the dissolution of the body one is bound for a happy destiny.

from the book: Emptying

the Rose Apple Seat

Sayadaw U Rewata Dhamma (4 December 1929, Thamangone – 26 May 2004, Birmingham) was a prominent Theravada Buddhist monk and noted Abhidhamma scholar from Myanmar (Burma). After pursuing an academic career in India for most of two decades, he accepted an invitation to head a Buddhist centre in Birmingham UK, and over the next three decades gained an international reputation as a teacher of meditation and an advocate of peace and reconciliation.